DRIVING AROUND TOWN ON pre-vacation errands in early August, I dropped by Lawler’s Liquors to check a few items off of the liquid supplies list. This old faithful of Napa bottle shops is one of our little wine city’s go-tos for both grain and grape booze.

Since the onset of these fun pandemic days, Lawler’s owner, Peter Ibrahim, has gone artisanal on his customers. That is, the center aisle of his family’s medium-sized store is still filled most late afternoons with vineyard guys waiting to pay for their 12-packs of Bud or Miller Lite, as was the case six months ago and forever before. Lately, however, the shelves have been lined with a wider and more eclectic variety of spirits labels than I probably ever expected to see. They call out to a different audience.

Standing behind the (now plexiglassed) register, one of Peter’s employees nodded appreciatively as he rang me up for my fancy choices of rye whiskey, London gin, and Spanish vermouth. When I commented on the shop’s diverse range of spirits, he mentioned that the boss was doing his part to support the local liquor distributors. With several beer-toting, thirsty-looking customers behind me, he left it at that. But in this depressing time of closed or struggling restaurants everywhere you look, the implication was clear that retailers were picking up the pieces, some of which were rather shiny and new—or in certain cases, dull and black. More on this in a second.

Back at home, into the cocktail bag went the deluxe provisions, along with some lemons and limes, bitters, bar tools, and other accoutrements. Then we hit the road the next day for Lake Tahoe.

Back at home, into the cocktail bag went the deluxe provisions, along with some lemons and limes, bitters, bar tools, and other accoutrements. Then we hit the road the next day for Lake Tahoe.

I am nobody’s rye whiskey expert. The most interesting thing I can tell you about Bulleit 95 Rye, which is one I like quite a bit, is that it’s made a stone’s throw from the Indiana-Ohio border, on the Hoosier side: a semi-bucolic area I once drove through while detouring between Indianapolis and Cincinnati, where everything south of the nearby Ohio River is the great Commonwealth of Kentucky.

This tri-state section of the U.S. has a more logical connection to all things whiskey than, say, a former naval shipyard here in the Bay Area. Maybe Dave Phinney, whom the San Francisco Chronicle has described as a “wine mogul,” will annex the region someday. In the meantime, this marketing genius acquaintance of mine is making his distiller’s play in Vallejo.

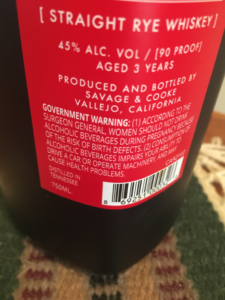

About 18 months ago, the St. Helena winemaker and well-known mind behind The Prisoner and Orin Swift wine brands started to produce Lip Service, a rye whiskey he and Master Distiller Jordan Via bottle at his Mare Island distillery, Savage & Cooke. It’s part of a trio of whiskeys that, to launch the boutique label, they procured from Kentucky, Indiana, and that other whiskey-centric state, Tennessee.

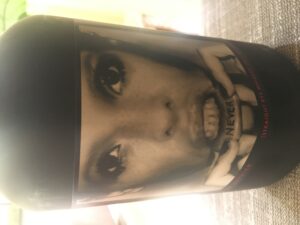

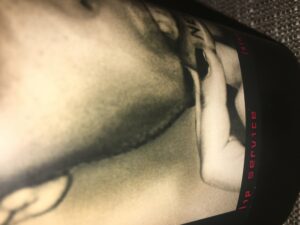

For the most part, the term “bottled” suggests a cylindrical vessel; Dave and his people put their whiskeys into the glass supplier’s equivalent of a lead ingot: the bottles are squat and opaque—basically a cube of light-absorbing blackness with four convex sides and rounded edges. The artsy-edgy label (a Phinney signature feature) actually decorates a corner, as opposed to a side, which makes for some clever presentation on a store shelf.

According to Lauren Blanchard, Dave’s general manager at Savage & Cooke, her boss designed the custom glass mold himself. “I’d describe it as a modern, blacked out bottle with a high-design feel,” she wrote me in an email.

I’d call it one of the most bad-ass booze packages I’ve come across. You’d rather drop a magnum of Champagne on your foot. I feel guilty tossing these sturdy, matte fifths into the recycling bin, instead of keeping them next to our emergency crank radio and filled with fresh water in case of a natural disaster.

And the label, oh boy. See pic.

“When you go to metropolitan areas, people are more familiar with Dave Phinney and his wines, and they’re more acclimated to his style of branding,” Virginia Haake told me over the phone recently. I’d called my ex-Napa Valley friend to chat about her experiences selling (and sipping) Lip Service rye in North Carolina, where she lives, and in the regions she covers as one of Savage & Cooke’s sales and marketing managers. These include many rural places on both sides of the Mason-Dixon line.

“When you go to metropolitan areas, people are more familiar with Dave Phinney and his wines, and they’re more acclimated to his style of branding,” Virginia Haake told me over the phone recently. I’d called my ex-Napa Valley friend to chat about her experiences selling (and sipping) Lip Service rye in North Carolina, where she lives, and in the regions she covers as one of Savage & Cooke’s sales and marketing managers. These include many rural places on both sides of the Mason-Dixon line.

“Getting out into the less urban areas, you know, some of the labels are a little bit more shocking, especially in the whiskey world, where a lot of people are more used to the traditional style of bottles and labeling.”

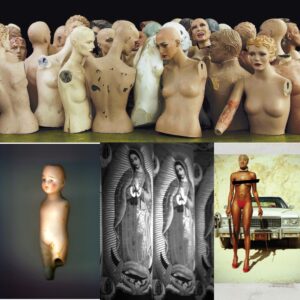

Dave’s provocative label art, whether adorning the Orin Swift wines or Savage & Cooke’s black bottles, is anything but traditional. Virginia confessed that, in her experience, some rural folks can be turned off by the colorful imagery. “It’s an interesting conversation to have with different groups of people because you certainly see those who aren’t as excited about it until they taste it.”

Now an experienced road warrior for S&C, she enjoys talking her customers through the aging process the rye goes through on its way to bottle. This includes a final few weeks in barrels that previously held Roussillon grenache at Dave’s Department 66 winery in Maury, France—another of the restless vintner’s many ventures. The French casks augment American oak barrels used at the Mare Island distillery, giving the rye a further degree of complexity.

Rye whiskey’s first cousin, bourbon, is probably better known for the oak-aging process that gives it its amber color and sweet flavors. For rye, according to the Whiskey Advocate website, “[a]side from its mashbill, the requirements … are identical to bourbon.” Again, not being an expert on it, rye seems lighter to me, with the sweet oak flavors less of a factor than the distinctive taste of the grain itself. Dave’s version is no exception.

Rye whiskey’s first cousin, bourbon, is probably better known for the oak-aging process that gives it its amber color and sweet flavors. For rye, according to the Whiskey Advocate website, “[a]side from its mashbill, the requirements … are identical to bourbon.” Again, not being an expert on it, rye seems lighter to me, with the sweet oak flavors less of a factor than the distinctive taste of the grain itself. Dave’s version is no exception.

“It’s a finishing thing. We’re constantly refining it,” he told me over the phone, carving out some time on a Friday afternoon to fill in some of the Lip Service backstory. The re-purposing of those Department 66 barrels had me particularly intrigued. “We did a ton of experimentation to figure it out because when we first started doing this, I said, ‘Look, this can’t just be some gimmick. If it doesn’t make it better, we’re not doing it.’”

Out in the world of whiskey aficionados on the retail and restaurant side, where the bullshit meters are, I would guess, well-calibrated to sniff out gimmicky whiskeys and the like, such products can’t have much of a chance against high-quality spirits. It stands to reason this is doubly true in my friend Virginia’s whiskey-soaked territory. As she noted with confidence, “The minute the rye is in their glass, and you talk to them about the product and the finishing of it in Dave’s wine barrels, their mind is quickly changed.” But only once they’ve tasted it, she emphasized.

Out in the world of whiskey aficionados on the retail and restaurant side, where the bullshit meters are, I would guess, well-calibrated to sniff out gimmicky whiskeys and the like, such products can’t have much of a chance against high-quality spirits. It stands to reason this is doubly true in my friend Virginia’s whiskey-soaked territory. As she noted with confidence, “The minute the rye is in their glass, and you talk to them about the product and the finishing of it in Dave’s wine barrels, their mind is quickly changed.” But only once they’ve tasted it, she emphasized.

“For the rye, it’s grenache barrels. They just add complexity, and it’s different with every spirit,” Dave explained on our call. He compared it to the tequila they produced until recently at Savage & Cooke. “When we made that, we used chardonnay barrels because it worked better. I think the bourbon is more cabernet. But it’s just nuance and complexity, and it does make a difference.”

He described various barrel experiments lasting from weeks to months as he and his team tried to nail down a formula to layer a bit of extra complexity into the mashbill—the distiller’s term for the grain ingredients. To make Lip Service, it’s fifty-one percent rye—the minimum amount of the grain allowed—plus forty-five percent corn, with a little malted barley to round out the recipe. In the end, as his GM Lauren confirmed for me, the spirit gets 40 days of additional aging in the Department 66 barrels after three years in charred American oak.

Virginia, whose job it is to communicate the Savage & Cooke whiskeys’ attributes to her clientele, didn’t hold back on her appreciation for how it’s made. “The finishing in Dave’s grenache barrels from France is definitely very unique,” she said. “So, that gives it some subtle, spicy notes to complement the fifty one percent rye. Most ryes, you know, have a higher percentage of rye grain in them.”

“Some people can be a little bit shocked when they try the spicier ryes. I think Lip Service lends itself to people who are wanting to kind of dip their toe into it.”

• • • • •

Backwoodsmen, country folk, and even a few city-dwellers might register varying degrees of shock when looking at a Dave Phinney-conceived label for the first time. Some of the images could double as stills from a Quentin Tarantino shoot. With Lip Service, the proprietor keeps the visuals moving in a fun, if slightly unsettling, direction.

To this end, he confessed, “Sometimes I have to remember who my audience is, and just because I like something doesn’t mean that everybody’s going to like it.”

To this end, he confessed, “Sometimes I have to remember who my audience is, and just because I like something doesn’t mean that everybody’s going to like it.”

There’s a not-too-subtle touch of sexy danger built into the Wakanda-esque tattoo photo on the Lip Service label. Meanwhile, the back label is all business: next to a barcode and government warning, it reads (in equally small print) “Distilled in Tennessee.” This discrete notation is Savage & Cooke’s disclosure, for the time being anyway, that the spirit in the bottle didn’t originate on a Vallejo island.

“As soon as we can, we’ll call them California whiskey, California rye, and California bourbon,” Dave told me. Not naming any names, he pointed out that some other artisan distilleries around the U.S. that have gotten busted over the last few years for buying finished whiskeys from the huge Midwest Grain Products operation in Lawrenceburg, Indiana and then labeling their products in misleading fashion. Bulleit acknowledges on their own back label of the 95 Rye that it’s distilled in Lawrenceburg. Though they leave out any MGP mention, as Forbes noted in a drinks article in April of last year, “the whiskey is distilled at the MGP plant in Indiana.”

“Now we’re distilling, rye, bourbon, and whiskey. But to have inventory and get started, you know, we did what pretty much everybody else does, which is buy barrels of finished goods. What we didn’t ever want to do was pretend like we didn’t.”

“The second lie is always worse than the first,” Dave laughed before we ended our call. “So, I just have no problem telling you that we purchased this as one- or two-year old rye and then aged it. And then we played with it.”

[End of Part One — Part Two, and my own rye whiskey cocktail recipe, coming soon.]