A FEW YEARS AGO, I flew into Houston for a work trip on a breezy October afternoon and cabbed straight to a sales appointment with a distributor colleague at a truly Texas-sized grocery store. No need to mention the store by name, though gourmet-minded residents of the city would know the place, which was high-end and located in a nice neighborhood. The lighting and space were bright and airy, and the shelves were very well-stocked. It reminded me of a saying I once heard: “Dallas has the flash, but Houston has the cash.” Indeed, there was a fossil fuel-enabled vibe of prosperity to this mammoth epicurean outlet. I was, after all, in the energy capital of the world.

Upstairs in a back office, the wine-related dealings came to a swift conclusion. The store’s merciless buyer was like the Astros’ J.R. Richard, circa 1978, shooting BBs past the Dodgers. Naturally, I was the Dodger—a strikeout victim. As I trudged back downstairs with my colleague, we encountered a wide stack of wine at the end of the “Gourmet to Go” aisle, the cases full of what turned out to be an Italian pinot grigio.

In keeping with the U.S. treatment afforded to one of Italy’s cornerstone exports, the boxes had been dumped directly from their pallet onto pinot grigio’s natural terrain in this country: the floor of a supermarket. The signage atop this lowly stack of wine advertised something called “Mommy’s Timeout,” its cost per bottle just a couple dollars more than Two Buck Chuck’s. There was no doubting this fancy store had more than a few cheapskates among its affluent clientele, and I was pretty sure that the pale liquid in the bottles didn’t exactly represent the noblest Italian expression of pinot grigio. But not curious enough to buy one on the spot, and not having come across this wine since, I can’t comment on its flavor (or possible lack thereof). It was really the label that caught my attention.

The illustration on it depicted a café table and a single, unoccupied chair arranged in the corner of a room. This being a timeout, the chair was pointed towards the corner, its shadow cast low against the wall. A bottle of wine and a glass sat on the table. I didn’t miss—or mind—the obvious humor. Here was the spot where Mommy could temporarily escape the stress of being a mommy and remove herself to a wine-themed break from the kids. It was clever visual marketing to a stressed-out demographic. But the image was also morbidly engaging. It reminded me of a Charles Addams cartoon: toss in an ashtray and burning cigarette, and it could have passed for a scene of foul play, or maybe the aftermath of someone’s spontaneous combustion.

• • • • •

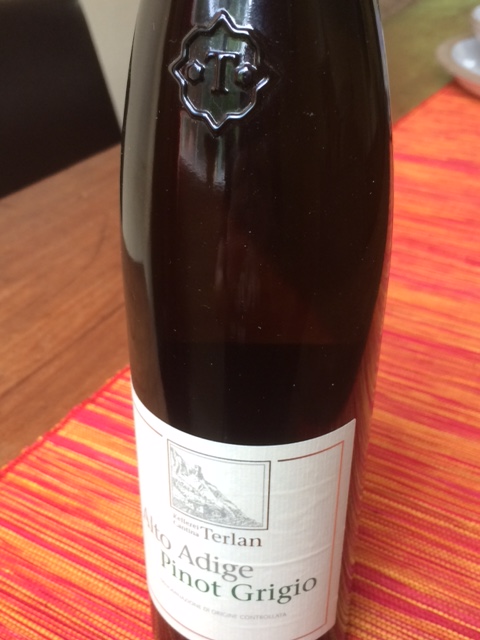

Though I appreciate the contents of a good bottle, I’m also a sucker for wine label art and packaging, particularly of Italian wines. They’re what drew me in the early 2000s to the distinctive bottles from Cantina Terlano, a winery in northern Italy. This historic company (which happens to produce excellent pinot grigio) is a 120 year-old cooperative of grape farmers in Alto Adige, the sundrenched province and winegrowing region in the Italian Alps, close to the borders of both Austria and Switzerland. Perhaps at some point the proud Terlano growers took a vote not to pallet-jack their slender, discreetly embossed bottles of pinot grigio into Texas grocery stores, fancy or otherwise. The postage stamp-sized Alpine etching at the top of the label would get lost in a supermarket, anyway. Cantina Terlano’s wines have always been a more unique Italian product, both aesthetically and from a quality standpoint.

“Everybody knows pinot grigio,” as my old friend Sean Diggins told me during a phone call in the spring of 2015, “but you have to qualify Terlano, because there’s an ocean of pinot grigio out there.”

Sean is the west coast sales manager for Banville Wine Company, Cantina Terlano’s U.S. importer. On our call, we talked about Terlano’s unique climate and long history, along with the terrific quality of the wines themselves. “I don’t mean that it’s only a high-end thing,” he clarified. “I just meant to say that if you’re lining Terlano up with pinot grigio in general, it’s a little tough.”

A day or two before we spoke, Sean had returned from Italy to his home in Oakland. He’d visited Cantina Terlano and Alto Adige’s capital city of Bolzano, highlights of the trip for his Banville colleagues and him. (The winery, he told me, takes its name from both the nearby town and the sub-DOC winegrowing region within Alto Adige.) Now, in advance of a turnaround visit to the Bay Area by Judith Unterholzner, Terlano’s vice director of sales whom I hoped to meet, I was curious what he’d learned about the winegrowing side of Alto Adige and the co-op’s delicious wines, in particular. As I mentioned, I’ve been a fan of the whole Terlano package—the wines, embossed bottles, and artful labels—since first being introduced to it in 2000. I wanted to dig deeper into the story.

Whatever its packaging or presentation, a wine’s main appeal lies in its aroma and flavor, characteristics unaffected by the label on the bottle, or even the bottle itself, but having everything to do with vineyard site, location, and climate. These physical factors have made Cantina Terlano a sought-after producer over many decades, despite that its wines come from a tucked-away region of Italy better known, perhaps, for its asparagus, apples, and nearby skiing.

Whatever its packaging or presentation, a wine’s main appeal lies in its aroma and flavor, characteristics unaffected by the label on the bottle, or even the bottle itself, but having everything to do with vineyard site, location, and climate. These physical factors have made Cantina Terlano a sought-after producer over many decades, despite that its wines come from a tucked-away region of Italy better known, perhaps, for its asparagus, apples, and nearby skiing.

“The area around Terlano is actually one of the sunniest places consistently in all of Italy,” Sean said, still a bit jet-lagged but happy to share pieces of information he’d picked up on the trip. “They get 300-plus days of sun a year, and that’s including Sardinia and Sicily and the warmer, southern parts of the country. Hence the grapegrowing, hence the crazy microclimate.”

He explained that the co-op’s growers practice viticulture under what could mistakenly be thought of as harsh mountain conditions, but it’s rather a cool climate, with mild, sunny days during the growing season and cold nights due to the elevation, which help develop the balancing components of ripe fruit and firm acidity in the grapes. Sean noted Terlano’s proximity to the large bodies of water that influence the local climate: the Mediterranean and Adriatic Seas to the southwest and southeast, respectively; and, at a closer 75 miles almost due south, Italy’s largest lake, Lago di Garda. Meanwhile, the jagged Dolomite range of the Italian Alps protects the Terlano growers’ vines and the surrounding Alto Adige region from northern Europe’s continental extremes of cold and hot weather.

The heading of a page on the co-op’s website reads, “Terlano – from mountains to palm trees,” and goes on to describe a place on Italy’s northernmost winemaking map where “Alpine peaks go hand in hand with Mediterranean scenery.” The strong hint of travel brochure copy doesn’t diminish the uniqueness of mountain grape growing within a climatically blessed part of Italy. As has gone on since Roman times, some of the country’s most outstanding viticulture and winemaking take place in Alto Adige.

• • • • •

For all of pinot grigio’s association with northern Italian wine, Cantina Terlano’s signature white wine is a traditional blend of pinot bianco, chardonnay, and sauvignon blanc called Terlaner Classico. At about 18,000 cases, or double what they make from pinot grigio, it’s the co-op’s largest-production bottling. As Sean pointed out, it’s been bottled since the winery’s earliest days and was Italy’s first DOC-regulated white wine produced from a blend of grapes. But vis-à-vis the variety’s international appeal and the wine’s moderate price, I believe Terlano’s calling card is still its pinot grigio.

One of Sean’s colleagues, Orange County-based Master Sommelier Peter Neptune, agrees with me on this—and then some. During a more recent conversation, the Senior Vice President for Wine Education at The Henry Wine Group enthused about Cantina Terlano’s range of wines, their extraordinary whites in particular: the pinot bianco from the Vorberg vineyards; the Quarz sauvignon blanc; and Nova Domus, a blend identical to the Terlaner Classico but brought to market after extended lees aging and time in barrel. His excitement on the phone only increased as he told me about the co-op’s Rarità (or “rarities”) bottlings of chardonnay and pinot bianco that are, somewhat incredibly, aged on their lees for a decade or more before release.

“I was buying the wines for myself, just as a consumer, and then I started working for Henry Wine Group,” Neptune told me. “Somewhere in the early 2000s, we began working with Banville, who of course are the importer of record for Terlano, and it was just like I was a kid in a candy store because then I got to go visit them, and I got to be intimately involved in presenting the wines.”

“The place is like Willy Wonka’s chocolate factory,” he laughed, describing one of his visits to the co-op and its vineyards. “It defies convention, what these guys are able to do. It’s the soil, no doubt: it’s the porphyric quartz [soil] and the fact that these guys just seem to know what they’re doing. Not to disparage their lagrein or any of their red wines, which are also delicious, but I think that dollar for dollar, pound for pound, they’re the best white wine producer out there, period. That’s my two cents.”

With his industry credentials, not to mention his polished phone demeanor (he’s a former television actor), Neptune’s two cents on Terlano’s top-of-the-line wines were worth quite a bit more than that to me. But I wanted to steer the conversation back down to the terrestrial level of pinot grigio, so I asked him where he thought Terlano’s fit into the picture, and if he agreed with me that it’s an exceptional bottling. He replied that he thinks their version is “a really solid example of Alto Adige. It’s got everything that a wine like that should have.”

“Pinot grigio’s the stuff that sells,” he added, commenting on what is probably the world’s second most popular white wine grape. “It’s an entry wine for most wine drinkers who are exploring Italian white wines. Obviously, the category is massively successful in the United States. I often ask myself ‘why?’ because most of the pinot grigio that people are drinking is insipid plonk. It’s like ‘alcohol juice-water,’ you know? But for the Terlanos out there, when you turn people onto a wine at that level, which is sub-$20 on the shelf, it’s a whole other level for consumers. Their eyes kind of get wide, and all of a sudden they’re tasting something that’s got real presence in the palate, and it’s got lingering aftertaste and minerality and all of those things.”

In a consulting role, Neptune is the wine buyer for Shutters on the Beach in Santa Monica, one of southern California’s more popular hotel-restaurants. He regularly features Terlano Classic pinot grigio as a by-the-glass offering. The property hosts scores of well-healed guests—Americans, of course, but also visitors from Europe and elsewhere—who partake enthusiastically in his wine program. As such, it’s among Terlano’s top wholesale accounts in the U.S. and is a place where Neptune’s (and my) theory about the quality of the co-op’s pinot grigio is put into practice every day.

“It does really well. It’s just one of those things that people really like it. Again, the category pinot grigio is going to sell, but you can either choose to pour the ubiquitous name brands, or something really cheap and insipid. Instead, Terlano offers something that’s affordable for by-the-glass at really high quality.”

Back up in Oakland, Sean at Banville knows all about this. He’s as experienced in wine wholesale as almost anyone in the Bay Area and has carried a wide range of pinot grigios and other Italian white wines in his salesman’s bag over the years, from bargains to blockbusters.

“In the whole realm of pinot grigio, it’s a little more expensive,” he noted in our call, “but it’s Terlano. People who are willing to pay for that don’t mind at all. For anybody who’s going to blind-taste it against any price point of pinot grigio, Terlano would stand out because it’s just a different expression, an incredibly beautiful wine. It would stand out anyway, regardless of price.”

“I’ll go see ten buyers, selling pinot grigio that day. Eight of the buyers have heard of Terlano, so they’re really interested, and the other two who haven’t heard of it become interested, based on the story and on me just kind of turning them onto it.”

Sean’s main job is to help his distributors sell the Banville portfolio to restaurateurs and retailers, interested and otherwise, up and down the west coast. In his sales pitches, he’s an expert at citing facts and figures about his suppliers’ products. But at the end of the day, it’s a hedonistic narrative. I think the actual calling of his position is to acknowledge wine’s inherently subjective nature and simply suggest or explain how a winery’s story and its wines’ compatibility with food align with each other. To this end, in conjunction with Judith Unterholzner’s Bay Area visit to promote her company’s wines, Sean organized a lunch at Great China Restaurant in Berkeley, and he kindly invited me. Not unlike Cantina Terlano, it’s an establishment known for quality ingredients, traditional methods, and precise execution of its product. It seemed like it would be a good fit.

[Two]

IN 2012, A FIRE WRECKED THE KITCHEN at Great China Restaurant’s former location in downtown Berkeley. Frankly, I think it was a blessing in disguise. The place was narrow and seemed a bit cramped when busy, which, owing to its much-deserved popularity, was pretty much all of the time. In early 2014, chef-owner James Yu and his family reopened a  couple blocks away on the corner of Bancroft and Fulton Streets. Here they had found one of the best urban dining addresses in the East Bay: the Cal Bears’ soccer and track stadiums sit kitty-corner, and Zellerbach Hall is close by. Thousands of pedestrians spill down Bancroft every day past this “new” Great China. Sleekly and sturdily constructed of concrete, wood, and glass in a style that my architect friend Warren Techentin calls “rough and ready ’90s material palette,” the restaurant is a front row seat to the comings and goings of the teeming UC Berkeley campus. Yet the northern Chinese Shan Dong dishes prepared in James’ kitchen are so good that, despite the big, east-facing windows, the picturesque Berkeley hills off in the distance, and some interesting people-watching, all attention seems to draw back inward to the glistening platters and steaming bowls that land on the tables.

couple blocks away on the corner of Bancroft and Fulton Streets. Here they had found one of the best urban dining addresses in the East Bay: the Cal Bears’ soccer and track stadiums sit kitty-corner, and Zellerbach Hall is close by. Thousands of pedestrians spill down Bancroft every day past this “new” Great China. Sleekly and sturdily constructed of concrete, wood, and glass in a style that my architect friend Warren Techentin calls “rough and ready ’90s material palette,” the restaurant is a front row seat to the comings and goings of the teeming UC Berkeley campus. Yet the northern Chinese Shan Dong dishes prepared in James’ kitchen are so good that, despite the big, east-facing windows, the picturesque Berkeley hills off in the distance, and some interesting people-watching, all attention seems to draw back inward to the glistening platters and steaming bowls that land on the tables.

Adding to the trauma the Yu family endured in 2012, smoke damage from the fire ruined a wine collection that James and Mark Yatabe, a Berkeley software designer who moonlights as the restaurant’s beverage director, assembled over five years. They’d put together an impressive inventory of California and European wines, a surprisingly rare accomplishment for a Chinese restaurant in the wine-centric Bay Area. With it, they managed to win their customers over to the concept of a meat-and-seafood-driven menu matched to a wide variety of wines. Five years later, they’ve rebuilt the list to about 200 selections, a very respectable offering but a fraction of the nearly 600 labels they cellared at Great China before the fire.

“We’re not even halfway to building it up, in terms of selection,” James told me recently while his staff sat down for a meal at one of the restaurant’s large tables after a busy lunch service. “But I feel like our choices are better this time around. It’ll be built in a better way, more geared towards the food.”

The 36 year-old chef explained how, in the transition to the new location, he and Yatabe decided to swap the cabernet-heavy Bordeaux section of the previous wine list for more pinot noir (and chardonnay) from that other notable French wine region, Burgundy. In his opinion, it made for a wine program better suited to his family’s traditional Shan Dong cooking. It was also “just more up-to-date,” as he put it. “The Bordeaux wines that we have are only going to be the new-school producers that are doing interesting things, but the Burgundy side is extensive, because it just goes well with the food.”

James’ interest in carrying pricier French wines like Burgundy and Bordeaux had me wondering, as it did when I spoke with Peter Neptune, what he thought about pinot grigio and less-expensive bottles from Italy. I had already been to Great China numerous times and noticed that such wines found their way onto his list.

“We like to do Italian whites with the food, in the crisp, dry style,” he said. “We’re not going after anything with residual sugar, really, though every now and then you might see something with a touch of RS on it. But the whites are generally pretty dry.”

While sales of California bottles at the restaurant have always been strong, he confessed that, as both a wine lover and restaurateur in the 510 area code, nothing made him happier than seeing his guests open up to other drinking possibilities from Yatabe’s and his selections.

“I want customers to explore more on the Great China list. We’ve always had California wines, but I like to keep a spread, and I won’t force it if it doesn’t work stylistically. Berkeley people are more receptive to having European white wines available, I think because of Kermit [Lynch Wine Merchant] being in town for so long, and because we have  a lot of importers here. People here are very open-minded, and Berkeley is a very wine-friendly town. It’s not the place where they sell tons of Rombauer.”

a lot of importers here. People here are very open-minded, and Berkeley is a very wine-friendly town. It’s not the place where they sell tons of Rombauer.”

In contrast to that gargantua of California chardonnay, he described Alto Adige white wine as “definitely a good tool to have, in terms of pairing.”

“They just go well with the food. White wines in general go better with my food than red, and the Italian offerings are so good for the price that they’re hard to pass up. So, these wines are very friendly for customers, you know? They’re very easy to drink and are also kind of fun because people don’t know about them all of the time.”

James echoed what both Sean Diggins and Peter Neptune said about the sale-ability of Terlano’s pinot grigio. Whether or not a quality Italian white wine was discernible to a Great China customer perusing the list, it fit neatly into an established category. Then, in the glass and with food, an elegant and complex pinot grigio or comparable wine quickly met and exceeded all expectations. When he planned the lunch for a group of East Bay retailers and restaurant wine buyers, Sean had a good feeling that the entire lineup of Cantina Terlano wines would complement Great China’s menu, and vice versa. Ever the food-meets-wine guy, he put himself in James’ hands.

• • • • •

On the afternoon of the Terlano lunch, I arrived a few minutes late but still had a seat next to Judith Unterholzner, Cantina Terlano’s Vice Director of Sales and Marketing. She introduced herself around the table while Sean poured welcoming glasses of 2013 Winkl, a single-vineyard sauvignon blanc the co-op has produced since the 1950s. Judith’s English is excellent, though she speaks it with a uniquely inflective accent, as might be expected of someone native to a part of Italy that is culturally Germanic. Born and raised in the town of Terlano, she half-jokingly described herself as “100% Alto Adige DOC.” The 30 year-old started at the winery in customer service and retail in 2004. After switching to the marketing side six years later, she worked her way up to her current vice director position. She travels the world as an ambassador for the co-op’s wines but lives only a short walk from its cellar doors.

On the afternoon of the Terlano lunch, I arrived a few minutes late but still had a seat next to Judith Unterholzner, Cantina Terlano’s Vice Director of Sales and Marketing. She introduced herself around the table while Sean poured welcoming glasses of 2013 Winkl, a single-vineyard sauvignon blanc the co-op has produced since the 1950s. Judith’s English is excellent, though she speaks it with a uniquely inflective accent, as might be expected of someone native to a part of Italy that is culturally Germanic. Born and raised in the town of Terlano, she half-jokingly described herself as “100% Alto Adige DOC.” The 30 year-old started at the winery in customer service and retail in 2004. After switching to the marketing side six years later, she worked her way up to her current vice director position. She travels the world as an ambassador for the co-op’s wines but lives only a short walk from its cellar doors.

I slid quickly into my seat, trying not to disturb the conversation as I turned on my recorder and placed it near Judith’s chopsticks. Displayed on the table between us was a small wooden box with Terlano’s familiar logo—the Alpine vineyard image from the wine labels—branded across its open lid. In the box sat several fist-size rocks of different colors and textures, examples of some of the soil types that make up underlayers of vineyards in Alto Adige. These include Terlano’s own purple-red volcanic porphyric quartz, the soil Peter Neptune would later mention to me in reference to the white wines’ extreme ageability. The little box, it turned out, was Judith’s handy visual aid. It came along wherever she traveled for work and helped her explain what makes Cantina Terlano such a unique operation.

With wine and lunch included, this was show-and-tell for grownups. “The quartz sediments as you see are those gray and white dots,” the vice director said about the speckled porphyric stone as it passed from buyer to buyer around the table. A first course of Shan Dong dumplings filled with fish and napa cabbage arrived from the kitchen while I sipped my glass of Winkl and inspected the claret-colored rock. It looked a little like a lumpy, dried-out sponge.

Off the bat, Judith addressed Terlano wines’ slow development in the bottle and cellar. “The combination of the Alpine climate and the minerality from the soil dissolved in the wines is a stabilizing backbone that allows us to mature our whites, not just for years but even for decades,” she explained. To demonstrate this, she brought along a magnum of 2004 Vorberg Riserva pinot bianco, which waited in a bucket at an adjacent table. She’d selected this mature bottle to challenge the notion that white wines don’t age well. “The longer you’re patient with our wines, the more they open up and the more multi-faceted they get. This is what Terlano is really well-known for, especially back home in Italy.”

Sean followed the sauvignon with 2013 pinot bianco, a sibling to the Terlano pinot grigio in the Classic line of entry-level bottlings. Indeed, I thought of it as that wine’s sexy older sister: fuller-bodied with more personality, though the family resemblance was unmistakable. Judith herself referred to the pinot bianco as “entry-level,” but she noted that the winery doesn’t endorse this terminology.

“We already have quite a high quality standard for the Classic whites,” she said, detailing Terlano’s rigorously selective grape harvesting across all quality levels of wines it bottles. “We’re doing not the 12,000 kilos per hectare as the maximum yield, which is legally allowed to be called DOC, but we have been voluntarily reducing the quantity to only 9000 kilos for nearly two decades.”

The Classic pinot bianco and Winkl sauvignon shared some of the hallmark characteristics of very good white wine made from low-yielding vines in a mild, diurnal climate: vibrant acidity; spicy and expressive fruit; and a concentration of flavors that played well with equally flavorful food, in this case the ingredients of a traditional Chinese menu. The wines were, to my palate, about as focused as could be while still retaining some of Terlano’s more ethereal qualities of minerals and earth.

“So,” Judith continued while she passed me a dumpling, “even for the Classic range, to guarantee a higher quality standard, we’re working with a third less fruit from our growers than we legally could do. Obviously, the higher we move up on the quality permit, the higher is also the quality of their primary fruit.”

She raised an interesting point: with its long history, Cantina Terlano has elationships with grape farmers that go back multiple generations. And in a contemporary setting of wine marketing and sales, these grower relations have taken on increased importance as the co-op continues to evolve its progressive—and successful—business model. She emphasized that her company has always had the growers’ economic interests at heart, perhaps never more so than now.

She raised an interesting point: with its long history, Cantina Terlano has elationships with grape farmers that go back multiple generations. And in a contemporary setting of wine marketing and sales, these grower relations have taken on increased importance as the co-op continues to evolve its progressive—and successful—business model. She emphasized that her company has always had the growers’ economic interests at heart, perhaps never more so than now.

“Terlano currently has 120 farmers, proprietors of just 370 acres of vineyards. They are all tiny, little micro-realities, and actually not even a handful of them are making their living from viticulture. Those who are 100% active in agriculture have apple orchards, which are located in the bottom of the valley, as the main income source.”

“The apples are really good, by the way,” interrupted a guest sitting near me who had been to Terlano.

“They are really good,” she agreed with a laugh. A waiter next served platters of salt and pepper prawns, and she focused for a moment on a unique category of Terlano growers. “Moreover, we also have a series of, as we call them, ‘Sunday-Sunday’ farmers: the families who received as a heritage from their parents just a few rows of vines around the house, and who continue working them, dedicating the leisure time, the after-work and weekend hours.”

Judith painted a pastoral picture but was careful to note that “it is really crucial to have clear rules of the game inside a co-op.” Beneath the quaint scene of a historic Alpine winery and its patchwork of garden vineyards, Cantina Terlano has a firmly drawn bottom line. “It’s a quality system which differentiates us from many other co-ops. We’re more than aware of the negative connotation that co-op organization quite often has. So, people directly associate the co-op concept with ‘Ok, high quantity, low quality.’ But, as the area itself is hard to work because of the mountain topography, most of the vineyards are really steep. It is important to have a high-quality production to guarantee our farmers also a fair income.”

The Cantina Terlano quality system, as Judith explained it, is a complex set of protocols laid out by the winemaking and viticultural teams. They’re overseen by enologist and head winemaker Rudi Kofler with an eye towards producing superior Alto Adige wine. The managers under Kofler are, she said, guided by “more than fifteen different parameters when calculating the individual purchase price for every single vineyard.” A large part of this value is determined by the winery enologist, who works to “verify the physiological, aromatic, and phenological ripeness” of the grapes. Meanwhile, Terlano’s agronomist visits every grower’s property several times during the year to be “active as a consultant and suggest somehow to improve, and also to mark the performance of the vineyards.”

“So, the rules of the game are clear,” the vice director reiterated. “The growers know how we want them to do the various work, within when and in which way the different tasks must be accomplished, but they get also a mark for their performance. And those marks are essential when we are then calculating the purchase price.” Pausing for everyone to digest this information, she smiled widely and joked that “it certainly reminds you all of the years at school.” If Judith Unterholzner was hiding an inner college professor, she revealed herself during lunch next door to UC Berkeley.

She then gave a small sigh and confessed that the arrangement is “quite complicated, and, as most of our Italian clients say, a very ‘Germanic’ way of organizing everything. But this is, for sure, due to history. Alto Adige has been part of the Italian state not even for 100 years. We were part of the Austrian empire till the end of the First World War, and only in 1918 our region was annexed by Italy.”

“So,” she summed up, “culturally we are certainly much more influenced by the Austrian-German background than by Italy itself.”

Several more Terlano wines made their way around the table, to the oohs and ahhs of Sean’s buyer guests (music, no doubt, to his salesman ears). In a Burgundian vein, these included the 2013 Kreuth chardonnay and 2012 Montigl Riserva pinot noir, special bottles I hoped Burgundy-loving James would have a chance to taste after the busy lunch service. The other red wine Sean poured, also from the ’12 vintage, was the nearly opaque Gries Riserva, Terlano’s structured version of the Alto Adige grape variety, lagrein. The two rich reds were delicious complements to James’ Peking Duck and Mei Cai Ko Ro, or pork belly cooked three times, and were happy exceptions to his rule that white wine goes best with the Yu family’s traditional cuisine. I was otherwise on board with this thinking, and never more so than when the best Terlano wines met Great China’s most sublime dish: Double Skin mung bean noodles.

Several more Terlano wines made their way around the table, to the oohs and ahhs of Sean’s buyer guests (music, no doubt, to his salesman ears). In a Burgundian vein, these included the 2013 Kreuth chardonnay and 2012 Montigl Riserva pinot noir, special bottles I hoped Burgundy-loving James would have a chance to taste after the busy lunch service. The other red wine Sean poured, also from the ’12 vintage, was the nearly opaque Gries Riserva, Terlano’s structured version of the Alto Adige grape variety, lagrein. The two rich reds were delicious complements to James’ Peking Duck and Mei Cai Ko Ro, or pork belly cooked three times, and were happy exceptions to his rule that white wine goes best with the Yu family’s traditional cuisine. I was otherwise on board with this thinking, and never more so than when the best Terlano wines met Great China’s most sublime dish: Double Skin mung bean noodles.

[Three]

THE PINOT GRIGIO I REFERRED TO as Cantina Terlano’s “calling card” is a relatively recent phenomenon at the co-op, having debuted in the late 1970s as a varietal bottling. Though ahead of the popularity curve, this wine would eventually become a drop in the “ocean of pinot grigio” evoked by Sean in our conversation last year. Not to ignore the complexity and charm Terlano’s winemakers have coaxed over many vintages from an over-produced grape, but as both Peter Neptune and Sean reminded me, Italian pinot grigio largely remains an expectations-lowering category of white wine. Still, for consistently transforming this variety into wine that such experts speak of with near-reverence, the Terlano team deserves a lot of credit.

Half a century earlier, in 1928, Cantina Terlano released its first vintage of pinot bianco. It’s fair to say the rest is history, since the vineyards established by preceding teams of growers and winemakers in the steep hills around Terlano have proven ideal up to the present day for producing rich, complex pinot bianco. From the Vorberg and Rarità bottlings singled out by Neptune down to the ’13 Classic version Sean poured to kick off the Great China lunch, pinot bianco is perhaps the best work that goes on at Cantina Terlano.

Judith’s magnum of 2004 Vorberg Riserva was a perfect and—if the reactions around the table were an indication—surprising example of this. Its crisp texture, taut minerality, and apple-citrus fruit flavors gave away no answers about its age. If anything, the freshness of the ’04 suggested a much younger pinot bianco. The mystery of the mature but lively wine in my glass matched that of the porphyric rock that sat on the table next to me: the volcanic quartz flecks on its surface and within the layers of Terlano soil it helped comprise had, by some viticultural miracle, combined with ideal weather and smart human intervention to produce yet another argument supporting the concept of terroir, or at least some vinous sense of place in a special corner of Alto Adige. I was drinking a piece of the puzzle.

Next to the ’04, the 2012 Vorberg Riserva was leaner and brighter, with a distinct citrus tang—though autumn notes of spiced apples and a stony backbone of minerals threaded it in my mind to the older bottle. Its vibrant complexity suggested that this pinot bianco had many years of development ahead. To me, these wines were the stars of the afternoon. As Neptune told me and has shared with a number of his fellow Master Sommeliers over the years, in his opinion the Vorberg vineyards produce “the greatest pinot bianco in the world.”

While Sean served this flight, Judith discussed how the Vorberg designation links to the physical location. “The vineyards are really steep,” she said of the growers’ terraced pinot bianco vines, planted at elevations between 1500 and 3000 feet. “And ‘Vorberg’ actually translated into English means nothing else than ‘pre-mountain.’ So, it even refers to the particular topography. The incline of those plots is from 20 up to 70 percent, and it’s really work-intensive.”

She smiled again as she related Vorberg to a local attraction. “Just to allow you to compare, the steepest section of Lombard Street in San Francisco has an incline of 43 percent, so Terlano’s vineyards are much steeper!” I pictured a bunch of Midwestern tourists in fluorescent windbreakers zig-zagging down a fog-shrouded Lombard on Segways—then transposed to the Dolomites in the back of a Pinzgauer, clinging to each other while Judith maneuvered them down Vorberg’s sunny inclines. The afternoon’s wine was fueling my imagination.

“These are all really sundrenched terraces,” she continued, interrupting my reverie. “The vineyards are extremely warm during the day, but cool at night due to elevation.” Swirling the younger pinot bianco, she seemed to capture its tension in her glass as she reminded the table that “it’s the [temperature swing] around Terlano which gives us this crisp acidity.”

Her mention of Terlano’s diurnal climate and the growing conditions Rudi Kofler and his team enjoy in Terlano had me recalling Sean’s impressions of Alto Adige and how well he thought the wines complemented the region’s Alpine cuisine. “With all of the acidity and spice and elegance, none of the wines were over-the-top in any way,” he said. “Even the ones they add oak to are very laid back and restrained. They lend themselves to a lot of foods, for sure.” The wines Sean poured during the lunch supported his opinion: I encountered a steady stream of bright, delicious, and balanced flavors that flowed as well with Shan Dong dumplings as they would have with Tyrolean knödel.

At this point, almost on cue, the menu item I mentioned earlier—Double Skin mung bean noodles—arrived at the table. James’ lineup of dishes certainly showed off his and his cooks’ skills in the kitchen, and also the compatibility of the co-op’s whites and reds in an atypical setting for Italian wine. But this unique Shan Dong dish presented alongside the Vorbergs signaled something a little more transcendent.

“Double Skin” is the Yu family’s in-house name for a Korean-influenced noodle recipe. The chewy, slippery noodles are made to order from mung bean flour, then mixed at the table with fried pork strips, wood ear mushrooms, sliced calamari and shrimp, cucumber, carrots, onions, and a piquant mustard sauce. “It’s a noodle salad, basically, the mung bean noodle we make fresh from scratch, every order,” James said of the layered preparation in our subsequent conversation.

He admitted that the recipe is fairly complicated compared to other Shan Dong specialties and that “it’s not something I grew up eating at home. Specifically, what I grew up eating, there’s nothing really elaborate, just really simple and good food. And when it’s simple, in fact, you’ve got to use good ingredients. There’s no margin of error.”

James described the bean flour as “really fine—it looks almost like corn starch.” To make an order of noodles, a slurry of water and flour is ladled into a stainless steel bowl that rests in a larger wok of boiling water. Then, some dexterity comes into play. “We spin the bowl on top of the water, and as the noodle travels, as the slurry and the momentum pulls it up the side of the bowl, it thins it out and it cooks it on the side of the bowl, and then we pull them out and we cut them up.” He noted that, if left to sit for as few as five minutes, the noodles “will gum up into a big ball, and you won’t be able to get it apart. It’s one of the harder noodles to make—but quick, if you know how to make it. It just takes a lot of experience.”

The same rule seems to apply to the Great China server tasked with serving Double Skin to guests at the table. It arrives as a platter of wiggling, semi-translucent noodles that were mostly liquid just a minute or two earlier. The rest of the ingredients are arranged in a circle around the noodles, and it’s the waiter’s job to deftly toss everything together in the sharp mustard sauce. I’ve had Double Skin a number of times, and James’ servers always make it look easy, the way a skilled waiter at a French restaurant makes removing the delicate bones of a whole fish appear as simple as folding a napkin. From the preparation in the kitchen to the methodical tableside service, the dish has an à la minute flair to it. I could tell by the details James shared that serving this wonderful Shan Dong creation to his guests made him happy.

“It retains this texture that has a little chew,” he said, “but it melts in your mouth. It’s kind of oxymoronic in that way, because it’s delicate, but it’s got ‘pull’ to it. It’s basically a fresh, flat cellophane noodle. It’s got seafood and meat and veggies, and it’s got a hot portion and a cold portion. It’s salty and spicy, and it’s got sour to it. It’s really about the textures and contrasts and the flavors that balance each other.”

“It retains this texture that has a little chew,” he said, “but it melts in your mouth. It’s kind of oxymoronic in that way, because it’s delicate, but it’s got ‘pull’ to it. It’s basically a fresh, flat cellophane noodle. It’s got seafood and meat and veggies, and it’s got a hot portion and a cold portion. It’s salty and spicy, and it’s got sour to it. It’s really about the textures and contrasts and the flavors that balance each other.”

Previous experience told me that these noodles were interesting and well-executed, with layers of flavor and texture from the many ingredients. But served alongside Judith’s pinot biancos, Double Skin became more than just the delicious sum of its parts: it was the most sublime thing offered that afternoon, a gastronomic partner to the complex Vorberg wines.

“Shan Dong is huge,” James told me when I asked him to put mung bean flour and noodles in the larger context of Shan Dong cooking, “and our palate comes from there, so everything gets filtered through it.” The region has a long coastline on the Yellow Sea, across from the Korean peninsula. In its cooking, both seafood and dough are important ingredients. “That’s why we make dumplings and things like that. It’s also the part of China—like where my grandmother comes from—where it’s the Chinese food that influences Korean-Chinese food, and vice versa, because it’s very close to Korea. So, yeah, our food is mostly based in those roots, but we’ve adapted it to what people expect from a Chinese restaurant in California in 2016.”

I realized that, though James and his family had upped their game to a certain degree at the new Great China, coming around “to what people expect” in the hyper-present of Bay Area dining didn’t represent any sort of compromise. The young chef regularly—and comfortably—fell back on his family’s culinary tradition to deliver elements of delight and surprise to his guests. One way or another, this is the goal of most chefs. Over lunch at this striking Berkeley restaurant, with a lovely view that almost no one noticed, the Shan Dong noodles were a singular menu item that lifted to new heights some equally unique wines from the far-away Italian Alps. Drinking from my glass of ’04 Vorberg and digging into the Double Skin, I felt very fortunate to be there.

[Afterword]

I was back in Houston last June, this time during a massive high-pressure weather system that affected a wide swath of the southern U.S. Texas was a sweltering mess. So much for October breezes, and the falling oil prices suggested the city might be on its way to becoming the former energy capital of the world. I looked for the cleverly creepy Mommy’s Timeout label in a couple of the high-end grocery stores I visited but had no luck.

Happily, the trip was scheduled for the week after my daughter’s auspicious promotion from the fifth grade. To celebrate and get out of Napa on the Friday before Father’s Day, I had her come with me to Berkeley to walk our dog around the edge of the UC campus and say hello to James. We enjoyed an afternoon’s stroll down Telegraph Avenue, followed by a father-daughter lunch at Great China. Though the ten year-old was on her best behavior, her dad pretended it was a timeout and ordered a glass of Valle d’Isarco kerner—yet another minerally, mind-blowing Alto Adige wine—to go with prawns, pot stickers, and, of course, an order of Double Skin. It was busy in the restaurant that afternoon, and the kitchen must have been humming. But, being the start of the weekend in Berkeley, the wines were flowing, and James worked the floor like an experienced sommelier. As the platter of Double Skin arrived at our table, he stood close by with the chilled bottle of kerner and, with a smile on his face to match ours, watched his waiter twirl the colorful ingredients together and calmly spoon the noodles onto our plates.

Happily, the trip was scheduled for the week after my daughter’s auspicious promotion from the fifth grade. To celebrate and get out of Napa on the Friday before Father’s Day, I had her come with me to Berkeley to walk our dog around the edge of the UC campus and say hello to James. We enjoyed an afternoon’s stroll down Telegraph Avenue, followed by a father-daughter lunch at Great China. Though the ten year-old was on her best behavior, her dad pretended it was a timeout and ordered a glass of Valle d’Isarco kerner—yet another minerally, mind-blowing Alto Adige wine—to go with prawns, pot stickers, and, of course, an order of Double Skin. It was busy in the restaurant that afternoon, and the kitchen must have been humming. But, being the start of the weekend in Berkeley, the wines were flowing, and James worked the floor like an experienced sommelier. As the platter of Double Skin arrived at our table, he stood close by with the chilled bottle of kerner and, with a smile on his face to match ours, watched his waiter twirl the colorful ingredients together and calmly spoon the noodles onto our plates.

Very nice, sir. Good reading.