OVER THE YEARS, I’VE WALKED, trudged, and even climbed through my share of vineyards, but I can’t recall bringing as much of one home on the bottoms of my shoes as I did in late January, when I met up with Joel Peterson in Oakley.

OVER THE YEARS, I’VE WALKED, trudged, and even climbed through my share of vineyards, but I can’t recall bringing as much of one home on the bottoms of my shoes as I did in late January, when I met up with Joel Peterson in Oakley.

In an unassuming place near the edge of the Delta, it’s all about the sand.

The morning after an atmospheric river flowed across the Bay Area, I headed out to eastern Contra Costa County and followed Highway 4 along an actual river—the San Joaquin—to get to my destination, an eight-acre vineyard near the Oakley-Antioch border. This unlikely viticultural spot on the suburban map doesn’t have a formal name, but Joel has designated it Oakley Road Vineyard for the wine he produces from its old-vine mataro grapes.

While his relatively new Sonoma-based label, Once & Future, isn’t nearly a household wine brand in the tradition of Gallo, Kendall-Jackson, or Mondavi, the wine company he founded in the mid-70’s certainly is. Joel launched Ravenswood in 1976 with the intention, in his own words, of creating “a small, personal project, where I was going to make just fine, single vineyard-designated wines and nothing else” from sites around Northern California.

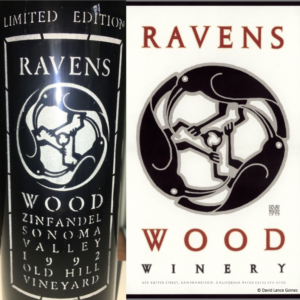

The distinctive trio of ravens interlocked in a circle, a Celtic-inspired logo created by the Berkeley artist and printer David Lance Goines in 1979, is one of California’s most recognizable wine labels. On his website blog, Bonny Doon’s Randall Grahm wrote in a post several years ago that the Sonoma winery has “without a doubt the most iconic logo in the business.” Goines’ arts and crafts aesthetic somewhat belies the image of a million-case winery, which Ravenswood eventually grew to by the time Joel had sold it to Constellation Brands in 2001.

Along the way, it’s fair to say he put his winemaker’s stamp on the concept of old-vine California zinfandel as firmly as the Gallo brothers did with their jugs of Hearty Burgundy, or Jess Jackson and Robert Mondavi achieved respectively with chardonnay and cabernet sauvignon. But the Ravenswood winery, which opened its wildly popular tasting room close to the Sonoma Plaza in 1981, was never named after its founder. In that way, Joel always flew under the radar, and to some extent he still seems to.

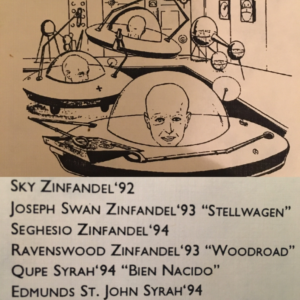

Perhaps such modesty engenders accessibility. When a couple of old friends in Sonoma clued me into the Once & Future wines last year, it reminded me of my own history with Ravenswood—the winery’s single-vineyard zinfandels in particular, which I bought, sold, and drank with great enthusiasm through the 1990s and early aughts in Berkeley and San Francisco. A pandemic check-in email from Kara and Adam, who I’d not seen in forever and happen to be Joel’s neighbors, prompted me to visit the O&F website, and from there drop a note to the zinfandel maestro.

In the mid-90s, the three of us worked together at Flying Saucer in San Francisco, a gone-but-not-forgotten Mission District restaurant where the chef-owner, Albert Tordjman, let me buy Joel’s pricier zinfandels as long as I also listed Châteauneuf-du-Pape, Crozes-Hermitage, and similarly spicy reds that honored his Moroccan-French ancestors. The Ravenswood wines from individual vineyards like Dickerson, Woodroad, and (especially) Old Hill were great foils for Chef Albert’s deeply flavorful cooking.

In the mid-90s, the three of us worked together at Flying Saucer in San Francisco, a gone-but-not-forgotten Mission District restaurant where the chef-owner, Albert Tordjman, let me buy Joel’s pricier zinfandels as long as I also listed Châteauneuf-du-Pape, Crozes-Hermitage, and similarly spicy reds that honored his Moroccan-French ancestors. The Ravenswood wines from individual vineyards like Dickerson, Woodroad, and (especially) Old Hill were great foils for Chef Albert’s deeply flavorful cooking.

After a follow-up email or two, Joel got back to me, noting my references to the Saucer and other places where I’d carried his wines, and invited me to meet him in Oakley for a walk amongst some seriously old zinfandel and carignane vines. But it was mainly to talk about mataro and the sandy soil in which it grows.

• • • • •

Consult the Bay Area Rapid Transit map and you can follow its yellow line up to the northeast quadrant, where it cuts through a wide swath of the East Bay and ends in Oakley… almost. BART’s actual terminus for this line is in the city of Antioch. Oakley is the next town over, and from there, heading east, Contra Costa County blends into the massive, marshy estuary of the Sacramento-San Joaquin River Delta.

Antioch and Oakley—a couple of Bay Area place names I’d associate with people and things not related to wine grapes: the latter being a sharpshooting frontierswoman, first name Annie, followed by a sporty and expensive brand of sunglasses; the former reminds me of the Holy Hand Grenade of Antioch lobbed by Graham Chapman’s King Arthur at the vicious bunny rabbit in Monty Python and the Holy Grail. The mythical king uses it to dispatch the “killer rodent” after it claws the faces of his Knights of the Round Table and, in gruesomely funny Python fashion, bites the head clean off one of them. A scene out of Watership Down it is not. But I digress.

Antioch and Oakley—a couple of Bay Area place names I’d associate with people and things not related to wine grapes: the latter being a sharpshooting frontierswoman, first name Annie, followed by a sporty and expensive brand of sunglasses; the former reminds me of the Holy Hand Grenade of Antioch lobbed by Graham Chapman’s King Arthur at the vicious bunny rabbit in Monty Python and the Holy Grail. The mythical king uses it to dispatch the “killer rodent” after it claws the faces of his Knights of the Round Table and, in gruesomely funny Python fashion, bites the head clean off one of them. A scene out of Watership Down it is not. But I digress.

At one of our local supermarkets, they regularly stock Cline Cellars’ Ancient Vines Mourvèdre, a juicy, well-priced Oakley red that has lately become a personal favorite. “We’ve been making mourvèdre out of Oakley for a number of years,” Charlie Tsegeletos, Cline’s now-retired head winemaker, told me over the phone recently. “It’s a great spot for mourvèdre—that deep, deep, sandy soil. The stuff’s all dry-farmed. We’re tickled to death with it.”

“Mataro” is a less fashionable synonym for the mourvèdre grape, an important Rhône and Provençal variety that Cline has worked with since the 1980’s, when it went into the Carneros winery’s Côtes d’Oakley bottling. This southern Rhône-style red blend was produced between 1986 and 1994 and was probably the first Contra Costa reference point for a lot of wine drinkers, including me.

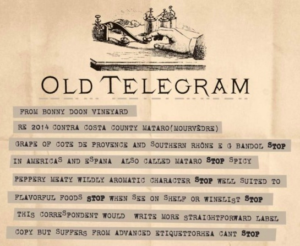

Of course, among wine geeks, no discussion of mataro/mourvèdre’s contemporary history in Oakley would be complete without mentioning (again, in this case) Randall Grahm and Bonny Doon. The original-cast Rhône Ranger made Oakley mataro under the quirky Old Telegram label for a long stretch of vintages from 1985 through 2018. He didn’t produce the wine in 2019, and then last year he sold Bonny Doon to a wine marketing company that discontinued the mataro bottling. But three-plus decades’ worth of Old Telegram is a very respectable body of work for an obscure grape from an even more obscure location.

“We started out with vineyards managed by the Clines,” Randall told me from the car after finishing an early April day in his vineyard down in San Juan Bautista. The large property in bucolic San Benito County is near one of California’s original Spanish missions; the Cline-managed vineyard in Contra Costa County was near a DuPont chemical plant. “We sort of used to joke that this is the wine that will give you the inner glow and the outer glow,” he laughed.

Joking aside, it was clear that he thinks Oakley was, and is, a superb source of mataro, the industrial surroundings notwithstanding. “That location was really great, and since then I’ve tried most of the mourvèdre vineyards in the Antioch-Oakley area. I’ve probably taken grapes out of ten or twelve of them, at least.”

During the few hours I spent in Oakley, I noticed less than half that number of vineyards in the vicinity of Oakley Road. Those I did lay eyes on reminded me that the “côtes” of Cline’s Côtes d’Oakley were probably meant to conjure up a pastoral wine country image à la France’s Côtes-du-Rhône. But at least a little tongue-in-cheek might have gone into naming it, as this agricultural strip along the shore of the San Francisco Bay had, by the 1980s, already seen the extreme, suburban transformation of much of its land, as had many other undeveloped parts of California close to urban centers like Oakland, San Francisco, and Los Angeles.

“It was not simply the huge growth in population that troubled the state,” Thomas Pinney writes in his second volume of A History of Wine in America, drawing an entirely different, post-agricultural picture of Oakley, but “the particularly American form of development that growth took—not urban but suburban.”

“It was not simply the huge growth in population that troubled the state,” Thomas Pinney writes in his second volume of A History of Wine in America, drawing an entirely different, post-agricultural picture of Oakley, but “the particularly American form of development that growth took—not urban but suburban.”

It was an expansion that the Pomona College professor emeritus notes “swallowed up thousands of acres of agricultural land” in California and included the East Bay counties of Alameda and Contra Costa. “Viticulture was not extinguished in these places,” Professor Pinney sums up, “but it was certainly put in danger.”

Today, the reality on the ground in Oakley is decidedly un-pastoral. It was one of the first things I figured out when I exited Highway 160 onto Main Street that morning to meet Joel at the vineyard. If his locus of Glen Ellen sits in a section of Sonoma wine country known as Valley of the Moon, I’d say the Antioch-Oakley corridor could get away with the nickname Valley of the Concrete.

• • • • •

In an email ahead of my drive down to the East Bay, the guy whose accomplishments at Ravenswood rival many of California’s greatest vintners’ shared something that surprised me: he was quick to express reverence for this little patch of vines in Oakley, an extremely humble place that’s anything but postcard-ready. “For me,” Joel wrote, “this location and wine were unexpected, which is saying something because in my 48 years of winemaking I have seen a bunch of stuff.”

Around the same time I sat down to begin working on this story, Rachael and I started watching the CNN food series “Stanley Tucci: Searching for Italy.” We’d been primed for the show by the network’s advertising following the January 6th QuackAnon jamboree at the U.S. Capitol—a cable advertiser’s gift that, sadly, kept giving on TV for several weeks (and of course came wrapped in a Pandora’s Box).

Midway through the series’ first episode, which takes place in Campania and focuses on that region’s cooking and gastronomic culture, the famous actor and his crew head outside of Naples for a visit with a San Marzano tomato farmer called “Uncle Vincenzo.” They’re covering the basics of Neapolitan pizza-making, and there’s a funny moment during Tucci’s narration when he’s about to arrive at the farm. “As a pizza-lover I only ever buy cans of San Marzano tomatoes, and now I’m heading to the promised land,” he says dryly, “although I hadn’t quite expected it to be a small farm under a freeway.”

He continues, “Behind Uncle Vincenzo’s rusty gates, I’m reminded that here in Italy, treasures are to be found in the most unlikely locations.”

While there was no Italian farmer to greet us on that cold, wet morning in January, Tucci’s lines resonated in relation to my visit, and I was instantly glad I’d recorded the series so I could give them a re-listen. The actor’s description echoed Joel’s own comment to me that he’d struck upon something very surprising in Oakley, an unlikely location that yielded a viticultural treasure from its sandy soil.

[End of part one — part two coming soon.]

Great piece. As a lover of mourvèdre (mataro) I’m in the natural demographic for this, but you’ve done so much more here than just scratch my mo-juice itch! VALLEY OF THE CONCRETE: GREAT TITLE. THANKS FOR WRITING THIS.

Excellent piece. Can’t wait for part 2..

Great read! Looking forward to part2.

Thanks, Sean!