FROM THE PANDEMIC THAT BROUGHT you virtual tastings comes another new addition to the wine lexicon: curbside pick-up.

FROM THE PANDEMIC THAT BROUGHT you virtual tastings comes another new addition to the wine lexicon: curbside pick-up.

And it’s quite new—for wine, anyway. As recently as February, “curbside” still implied a transaction likely involving a Chick-fil-A or a Big Mac. Just three or four weeks later, in-person shopping for wine—the quaint, familiar concept of browsing shelves and case stacks, picking up bottles to read their labels, maybe sampling at a tasting bar—had been pandemically turned on its head. A more appropriate metaphor might be kicked to the curb.

Or maybe not.

“It’s almost impossible to emphasize how different this landscape is right now,” my friend Dan Polsby wrote to me in an email in March about Vintage Berkeley, the College Avenue shop he manages and buys for, and now was tasked with converting to a 100% curbside pick-up business. “Some distributors and importers have already stopped shipping. Some are experiencing crazy delays. And for us? Basically every day right now is as busy as what’s usually our busiest day of the year—but at quarter staff, for 12-13 hours—despite letting no customers into the store. Can you imagine?”

Could anyone have imagined such a scenario? Besides that cohort of doctors, scientists, and other infectious disease experts (surely some wine enthusiasts among them) who’d been sounding the alarm to the White House about Covid-19 since January, I mean.

As I drove to Vintage Berkeley on a cloudy March morning to grab a box of wine, which included some Traboules, Guillaume Clusel’s singular Rhône Valley gamay, I marveled at the hunker-down mentality of Dan’s customers. I was merely out of my new favorite red. But from the alarmed tone of his email, it sounded like East Bay wine shoppers were starting to equate fermented grape juice with clean drinking water, or otherwise knew something that the Napa Valley guy did not. I drove a little faster.

Exiting the freeway in Berkeley, the store’s College Avenue curbside wasn’t on my mind. Per Dan’s instructions, this was to be more of a back alley transaction.

“Go through Wells Fargo parking lot, turn right, pull in first parking spot,” he wrote in a text. So I did, then picked up the box waiting for me, said a safe-distance hello to my friend, and was out of there like a People’s Park reefer customer, circa 1980. This was, I feared, the new face of bricks-and-mortar wine retail.

• • • • •

As long as I’ve been shopping at Vintage Berkeley, the Elmwood store has had a very good—and often great—selection of Beaujolais and other gamay wines. It seems to be an East Bay theme: shops like North Berkeley Imports, Paul Marcus Wines in Rockridge, Solano Cellars in Albany, Pleasanton’s The Wine Steward, and Berkeley’s Beaujolais mothership, Kermit Lynch, all cater to the gamay crowd. It makes sense: this section of the Bay Area is one of the gastronomic centers of the U.S., and, as my Paris restaurateur friend Tim Johnston says, “Gamay is the perfect grape to make easy-drinking, really gourmand and juicy wines.”

As long as I’ve been shopping at Vintage Berkeley, the Elmwood store has had a very good—and often great—selection of Beaujolais and other gamay wines. It seems to be an East Bay theme: shops like North Berkeley Imports, Paul Marcus Wines in Rockridge, Solano Cellars in Albany, Pleasanton’s The Wine Steward, and Berkeley’s Beaujolais mothership, Kermit Lynch, all cater to the gamay crowd. It makes sense: this section of the Bay Area is one of the gastronomic centers of the U.S., and, as my Paris restaurateur friend Tim Johnston says, “Gamay is the perfect grape to make easy-drinking, really gourmand and juicy wines.”

More specifically, what these shops have in common are the cru Beaujolais they carry on a consistent basis: wines from individual villages like Brouilly, Villié-Morgon, and Fleurie at the northern end of Beaujolais. The small region is close to Lyon, not coincidentally another gastronomic capital and certainly France’s most revered. There are ten crus in total, and they represent the best qualities that Beaujolais vignerons—helped by Mother Nature—can achieve through gamay in their viticulture and winemaking.

“[Y]ou will rarely see the word Beaujolais on a label of these” cru wines, Jancis Robinson points out in the gamay chapter of her encyclopedic website. She calls them “the region’s most articulate ambassadors,” a perfect description for the produce of those quality-driven vignerons who, like their pinot-farming neighbors in Burgundy, have raised gamay to an art form.

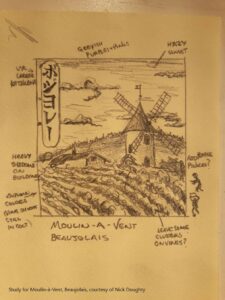

In my own occasional musings, Beaujolais is like jazz, and the grouping of ten unique crus is a bebop dectet—a ten-member ensemble, i.e. a rarity—articulating a lively but also thoughtfully crafted version of gamay. Fleurie on flute, Moulin-à-Vent on baritone sax.

But what of Traboules, the hard-to-find Rhône wine Dan had set out in the box for me?

To look at cru Beaujolais from another angle: if Brouilly, Chénas, Juliénas, and the rest of the villages were siblings in a large family, I think Guillaume Clusel’s Rhône gamay would be their first cousin from over the hills, but not too far away.

• • • • •

When Charles Neal and I talked back in January about this unusual wine, he was on a train in New York for a family visit.

In addition to bringing Clusel-Roch’s and other French wines and spirits to the U.S., the San Franciscan is an accomplished author, with long, deeply researched books to his name on Calvados and Armagnac. He’s also written two novels and a book about 1980s indie music. As a guy with varied interests and expertise, I figured he’d be willing to chat with me for this column, his travel schedule notwithstanding.

About twelve or thirteen years ago, the owners of a Bay Area importing company decided to change the focus of their wine sales business. The move, according to Charles, left a handful of small, high-quality French wineries they represented in the lurch. Clusel-Roch was one of these.

His friend and customer Gerald Weisl, the owner of Weimax Wines & Spirits in Burlingame, just south of San Francisco, helped convince him to start importing these orphaned wineries. Doubtless, Gerald (who’s an Italian wine expert but has probably also forgotten more about French wine than most people will ever know) pictured his old-school bottle shop without any Clusel-Roch Condrieu or Côte-Rôtie sitting on its shelves and couldn’t stand the thought of it. That underlying motive has worked to both of their customers’ benefit ever since.

His friend and customer Gerald Weisl, the owner of Weimax Wines & Spirits in Burlingame, just south of San Francisco, helped convince him to start importing these orphaned wineries. Doubtless, Gerald (who’s an Italian wine expert but has probably also forgotten more about French wine than most people will ever know) pictured his old-school bottle shop without any Clusel-Roch Condrieu or Côte-Rôtie sitting on its shelves and couldn’t stand the thought of it. That underlying motive has worked to both of their customers’ benefit ever since.

Charles recounted on the phone that back when Gilbert and Brigitte Clusel started working with him, their son Guillaume was in his teens. Later, around 2009, he started to learn the ropes from his parents and get incorporated over the next several years into the running of the domaine. As Tim Johnston noted about the Clusels in an email to me a few days before the phone call, “They have an immense wealth of wine-making knowledge to draw from as a family.”

Over the background noise of the train, Charles brought the Clusel-Roch story up to the present. The young man has become a young, married father who, in his opinion, is maturing into his role. “Guillaume is now maybe a real winemaker,” he suggested. And under his watch as a fourth-generation Clusel vigneron, “the wines have soared in quality since he’s put his imprint on the domaine.”

“You know, the way that I like to look at it, every generation that produces wine generally does something at their property to kind of make their statement on it,” he said. Traboules, launched under the family’s label, is a big part of Guillaume Clusel’s imprint: gamay is his Rhône Valley statement.

To get Traboules off the ground, Charles explained, “Guillaume basically bought—or rented, actually—a couple of vineyards up in the Coteaux du Lyonnais, which is about 20 or 25 minutes north of Côte-Rôtie and maybe a half hour outside of Lyon.”

In 2020, the Coteaux du Lyonnais is neither old nor new. Established in 1984, it’s still a rather recent appellation compared to many French AOCs. Only gamay is permitted for the red wines. Looking at the map of wine regions surrounding Lyon, it bridges the viticultural gap between the Rhône syrah grown to the south and the Beaujolais gamay up north.

Charles recalled visiting this region of hillside vineyards a decade ago and meeting with one or two producers. As an importer, nothing grabbed his attention back then, but he left with a distinct impression: “Gamay is the grape, and so it’s kind of like an alternative gamay to Beaujolais.”

Or, as Tim put it in his email, “It’s a sort of halfway house between the Rhône and the Beaujolais.”

My old Paris boss has enjoyed a long friendship with the Clusel family. After Guillaume debuted Traboules as a label, it found a warm welcome at Juveniles, Tim’s 1st arrondissement wine bistro. “We have been selling it since he started, and he and his father even took me to visit the vineyards,” he wrote when I asked him to share some thoughts on the wine.

“I love the Coteaux du Lyonnais, particularly Traboules. I think Guillaume Clusel is very intelligent. Most of the new boys on the block want to make Côtes-du-Rhone, or Saint Joseph, as their less expensive range of wine. By expanding the Clusel line to Coteaux du Lyonnais, Guillaume not only gets to farm land up on those high plateaux, but play with a different grape variety.” Besides syrah, he meant, which the Clusels excel at with their fantastic Côte-Rôties.

“He has approached the subject seriously, and this is singly one of the best value wines on the market today.”

From both Charles’ and Tim’s perspectives, Guillaume’s project is an earnest one, infused with a drive for quality matching that of many cru Beaujolais growers 50 miles to the north. From my back row seat far away in Napa, it appears he also had some fun with the name.

[End of Part Three – Part Four, “La Dernière,” coming soon.]