“Far-roving pioneer vintners from Europe carried with them the desire to create vinous echoes of their homelands.”

—Robert Lawrence Balzer, The Joys of Wine, 1975

ALMOST SINCE I STARTED drinking wine, I’ve thought of the mourvèdre grape in superlative terms.

Across borders in Spain and France and time zones in Australia and California, this thrilling, complex variety makes some of the wines—on its own and in combination with syrah and grenache—that I most enjoy putting in a glass.

Before that even happens, there’s the splendid fact of its name. Or, rather, all three of them.

The vine, which is best known in France and internationally as mourvèdre, started out as mataro in Spain before getting rendered into French. Then, somewhere along the line it became monastrell—a possibly neutral name created by, and for, the Spanish. Oz Clarke notes this in his Encyclopedia of Grapes.

According to the English wine writer, the name split the difference between Valencia and Catalonia, two Spanish regions closely identified with the vine—and whose respective towns of Murviedro and Mataró give a pretty strong toponymic clue to its dual identities. “Perhaps,” Clarke writes, “local pride meant that both areas claimed the grape so fiercely that Monastrell was chosen so as not to offend anyone.”

As a self-described wine cheapskate who’s hard to offend, I can share that most of my monastrell thrills over the years have been provided by reds from a third spot on the Spanish map, Jumilla. And they have been cheap, indeed. More on this in a moment.

As a self-described wine cheapskate who’s hard to offend, I can share that most of my monastrell thrills over the years have been provided by reds from a third spot on the Spanish map, Jumilla. And they have been cheap, indeed. More on this in a moment.

From Spain, mataro/monastrell migrated to France’s Provence region in the late Middle Ages, changing its name in the process. It’s a topic covered on the website of Tablas Creek Vineyard, which has a section dedicated to the backstories of the wide range of Rhône and Mediterranean grape varieties the respected Paso Robles winery grows and produces.

Separately, the UC Davis Integrated Viticulture website suggests that the Spanish vine first crossed over into the French Roussillon—still part of Spain until the mid-17th century—and became widely planted in that ancient viticultural region. In either case, its natural progression was eastward to neighboring Provence and the Rhône Valley, where both Oz Clarke and prevailing wine wisdom have it morphing from mataro/monastrell into mourvèdre.

While, according to Tablas Creek, a more recent “return to the French Mourvèdre name has given the varietal a new life” in places like California and Australia, its historic change of identity hardly alters the modern importance of the grape to Spanish viticulture. On the winery’s website, they point out that “more than 80% of [mourvèdre’s] worldwide acreage remains today” in Spain, where just over 100,000 acres of it are planted and where the vine “is second only to Grenache (Garnacha) in importance.”

While, according to Tablas Creek, a more recent “return to the French Mourvèdre name has given the varietal a new life” in places like California and Australia, its historic change of identity hardly alters the modern importance of the grape to Spanish viticulture. On the winery’s website, they point out that “more than 80% of [mourvèdre’s] worldwide acreage remains today” in Spain, where just over 100,000 acres of it are planted and where the vine “is second only to Grenache (Garnacha) in importance.”

With just over a thousand acres of mourvèdre currently planted in California, it’s not exactly going out on a limb to say that it’s a hundred times more important to the Spanish than it is to American wine drinkers.

As for this American, I think there might be a little Spanish in me. I know for sure that, while I’ve drunk my share of garnacha and other reds from both Valencia and Catalonia, overall I prefer monastrell—Jumilla monastrell, in particular.

This small winegrowing appellation, or denominación, sits within the Murcia  region, inland from the Mediterranean in southeast Spain. “Talking about the D.O. Jumilla means talking about the ‘Monastrell’ variety,” the appellation’s official website summarizes about its vineyards, the vast majority of which are planted with the fabulous grape. It also means talking about heady, full-bodied wines that are grown in a relatively hot climate and rarely set you back more than twenty bucks.

region, inland from the Mediterranean in southeast Spain. “Talking about the D.O. Jumilla means talking about the ‘Monastrell’ variety,” the appellation’s official website summarizes about its vineyards, the vast majority of which are planted with the fabulous grape. It also means talking about heady, full-bodied wines that are grown in a relatively hot climate and rarely set you back more than twenty bucks.

The monastrells bottled by two Jumilla wineries, Casa Castillo and Bodegas Juan Gil, are those with which I’m most familiar. They’re ridiculously inexpensive in relation to the deliciousness they bring to the table. Less affordable is Castillo’s “Pie Franco” bottling of ungrafted, old-vine monastrell. On the internet, this wine hovers around a hundred dollars; in Napa Valley cabernet money, you’d easily double that price tag. So, I guess “expensive” depends on your definition and budget.

wineries, Casa Castillo and Bodegas Juan Gil, are those with which I’m most familiar. They’re ridiculously inexpensive in relation to the deliciousness they bring to the table. Less affordable is Castillo’s “Pie Franco” bottling of ungrafted, old-vine monastrell. On the internet, this wine hovers around a hundred dollars; in Napa Valley cabernet money, you’d easily double that price tag. So, I guess “expensive” depends on your definition and budget.

• • • • •

“[N]o one except the Spanish uses the Monastrell name,” Oz Clarke writes in his encyclopedia, adding that “frankly, Mourvèdre is much more honoured away from its birthplace.”

Arguably, the place where the grape is honored most is in Bandol.

Unlike many Spanish versions of the grape, the mourvèdre-based wines of this great appellation in Provence aren’t cheap. Nor are they terribly expensive, but, again, that’s relative. More important, Bandol is certainly on any wine expert’s or enthusiast’s short list of the best uses of the variety.

Vis-à-vis the Bandols from the iconic winery, Domaine Tempier, that I had the good fortune to taste in my early 20s, mourvèdre landed rather spectacularly on my radar. Tempier’s most famous vineyards, La Migoua and La Tourtine, are planted with it—half of the former’s acreage and eighty percent of the latter’s—as are swaths of the Bandol appellation just inland from the Mediterranean seaside town of the same name, to the point where the vine and the place are almost inseparable. It’s not unlike monastrell and Jumilla, only with a climate that’s more Santa Barbara and less Palm Springs.

Vis-à-vis the Bandols from the iconic winery, Domaine Tempier, that I had the good fortune to taste in my early 20s, mourvèdre landed rather spectacularly on my radar. Tempier’s most famous vineyards, La Migoua and La Tourtine, are planted with it—half of the former’s acreage and eighty percent of the latter’s—as are swaths of the Bandol appellation just inland from the Mediterranean seaside town of the same name, to the point where the vine and the place are almost inseparable. It’s not unlike monastrell and Jumilla, only with a climate that’s more Santa Barbara and less Palm Springs.

As for California, the “new life” that the folks at Tablas Creek find mourvèdre to be enjoying maybe isn’t so new, after all.

In the mid-90s, a couple years after getting introduced to Bandol and a bunch of other French wines that use mourvèdre, I met the late winemaker Dick Graff while slinging wine on the job in San Francisco. Following a subsequent meeting to taste his Chalone Vineyard wines, he gave me a bottle of the Richard Graff Vineyard mourvèdre he was making at the Chalone winery near Pinnacles National Park in Monterey County. I can almost still taste that gamey-spicy wine, which even my novice palate must have recognized was very good. I wish I’d been doing this type of writing back then and had a chance to interview him.

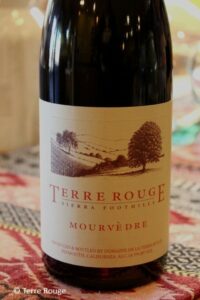

Around the same time I got acquainted with Mr. Graff, my friend and former boss Bill Easton harvested his first mourvèdre grapes from vineyards in the Sierra Foothills. Though the Richard Graff project was cut short by the winemaker’s untimely death in 1998, Bill’s Terre Rouge winery in Shenandoah Valley went on to earn a reputation, both in the U.S. and internationally, as one of California’s best sources of syrah and other Rhône variety wines. His acclaim as a winemaker has only grown during the last two decades.

boss Bill Easton harvested his first mourvèdre grapes from vineyards in the Sierra Foothills. Though the Richard Graff project was cut short by the winemaker’s untimely death in 1998, Bill’s Terre Rouge winery in Shenandoah Valley went on to earn a reputation, both in the U.S. and internationally, as one of California’s best sources of syrah and other Rhône variety wines. His acclaim as a winemaker has only grown during the last two decades.

Bill, who’s appeared in these pages before, has continued and expanded his signature program of single-vineyard syrahs. He still focuses on just one Terre Rouge mourvèdre bottling every year, however. The most recent I’ve tasted, from 2013, comes close to reminding me of a good Bandol—maybe more so than any California mourvèdre I’ve tried. Knowing the guy who made it like I do, it’s a welcome comparison. Bandol is something of a template for my old friend, and it gets mentioned on his bottles’ back label.

“Our mourvèdre’s vine age is around 30 years. The vineyard was planted in 1992, so the vines are pretty established.” Bill told me this over lunch in Napa back in late March. The pandemic still necessitated outdoor dining, and the weather was cooperating on the sunny but breezy day. We met for Spanish food at Zuzu, as good a place as any to get into a mourvèdre (or monastrell) frame of mind.

We tasted—er, drank—a couple of other wineries’ mourvèdres, including Joel Peterson’s Once & Future mataro that I recently wrote about here. The Sierra Foothills vines that Bill works with are at least 100 years younger than those of Joel’s ancient site in Contra Costa County, but he picked up a common thread between his fellow vintner’s wine, his own Terre Rouge bottling, and some Spanish and French versions of the grape.

“I think we get more of the earthy tones in our mourvèdre,” he said, “but we also get some of that kind of pure cherry or raspberry-like fruit that you get in the mountains of Spain, that monastrell kind of component. I see that in our stuff. It’s got a little more earth and funk than some other California mourvèdres.”

More recently, after I’d received a shipment of bottles from Bill’s retail manager at Terre Rouge, I sent him a text to tell him the ’13 mourvèdre was tasting quite nice, in a fashion consistent with his winemaking approach to the variety: cherries and raspberries are valid descriptors, but he doesn’t shy away from the non-fruit aromas and flavors that help define mourvèdre. The ’13 was in a sort of blue-fruity funk phase when Rachael and I drank it. “Sometimes I think American taste doesn’t appreciate the gaminess; some funk, earth, spice,” he texted back. “That wine rocks.”

As far as my rosé-loving wife is concerned, Bill’s mourvèdre would rock harder if it was several shades of pink lighter, but at least she tasted it.

• • • • •

Over the years, his collaborations with growers in the Sierra Foothills have meant that the grapes Bill sources for his wines come from higher elevation vineyards than most other California wineries’. Halcón Vineyards in Mendocino County is an exception. In the realm of viticultural superlatives, it’s a notable one.

Paul and Jackie Gordon planted Halcón in 2005 after searching in Mendocino County for a piece of property with a combination of soil and climate that would allow them to emulate their beloved wines of the Rhône Valley. The spot the couple found in the Yorkville Highlands AVA sits at a lofty 2500 feet and was, they reckoned, a great place to put in late-ripening mourvèdre, in addition to syrah and grenache.

Paul and Jackie Gordon planted Halcón in 2005 after searching in Mendocino County for a piece of property with a combination of soil and climate that would allow them to emulate their beloved wines of the Rhône Valley. The spot the couple found in the Yorkville Highlands AVA sits at a lofty 2500 feet and was, they reckoned, a great place to put in late-ripening mourvèdre, in addition to syrah and grenache.

“We planted our most sheltered, south-facing slopes to our Southern Rhône varieties, Grenache and Mourvèdre,” Paul wrote to me in an email earlier this year, describing the layout of the vineyard. “Our Syrah has more varied exposures—south to north—and is more exposed to the wind. Being an earlier ripener, the Syrah can tolerate the cooler areas.”

He reminded me that the mourvèdre and other vines were, at the time, only fifteen years old—“Just starting to enter their young adulthood,” as he put it. Surprised by this, I wrote back that it amazed me how relatively young vines like Halcón’s offered such depth of flavor and aroma. “Really well done,” I complimented him.

Paul seemed to appreciate my take on the wines, and I sensed pride in his tone when he got back to me next. “As you have likely seen, we always pick our mourvèdre very late,” he emailed. “By the way, I think we have the coolest climate planting of mourvèdre in the world. I have told many people this belief and I have yet to hear of a cooler planting.”

In the Gordons’ hands, the mourvèdre grapes’ naturally extended hangtime on the vines has translated to wines with enhanced characteristics that seem to reflect the extreme landscape: an intense and concentrated gaminess, with wild, black-and-blue fruit, angular tannins, and nervy acidity layered into the texture. I think I most like their mourvèdre because it’s a bit weird and possesses something hard-to-pin-down. In this way, it’s a reminder of the variety’s utter uniqueness. And while I only have experience drinking the 2017 and ’18, those vintages suggest to me a terroir characteristic specific to an elevation shared by vines and halcóns—Spanish for hawks.

Sadly, in advance of a move back to Europe in 2022, the English couple have put the Yorkville Highlands property up for sale. So, I’ve grabbed an assortment of their wines as a hedge against a Halcón-less future.

[End of Part One — A few words on some other exceptional mourvèdres coming soon in Part Two.]