ADELAIDA, AS THE ALLUSION to boxing goes, punches above its weight.

It may be one of California’s less familiar wine regions, but this mountainous, oak-studded viticultural area just outside of Paso Robles boasts a couple of the Central Coast’s signature wineries, along with a major industry player. About three dozen others comprise an eclectic roster of Adelaida wineries.

The district is home to Tablas Creek Vineyards, the innovative grower-producer of Rhône and Mediterranean grape varieties I’ve written about previously. Several scenic miles up the road is the more mainstream Daou Family Estates (stylized “DAOU” on their labels), which specializes in Napa Valley-ish red wines. With their respective national footprints, each winery serves an ambassadorial role for Paso Robles as an important source of California wine.

In my travels, Daou has often seemed to show up as a grocery chain and steakhouse standby, while Tablas Creek’s Rhône focus makes it more of a mom-and-pop establishment brand (if mom hummed along to Edith Piaf and pop sported the occasional beret). Each produces a hefty 30,000 cases per year, enough to satisfy distributor and direct-to-consumer needs many times over.

Adelaida’s heavyweight producer is the well-known Justin Vineyards, a cabernet-focused operation that’s basically Daou on steroids, with nearly ten times the production of it or Tablas Creek. Also branded in all caps, the JUSTIN label is part of the massive agricultural portfolio of The Wonderful Company, an ironically named mega-corporation whose adventures in California almond farming are the stuff of water-hogging legend.

Adelaida’s heavyweight producer is the well-known Justin Vineyards, a cabernet-focused operation that’s basically Daou on steroids, with nearly ten times the production of it or Tablas Creek. Also branded in all caps, the JUSTIN label is part of the massive agricultural portfolio of The Wonderful Company, an ironically named mega-corporation whose adventures in California almond farming are the stuff of water-hogging legend.

That most of the other wineries in this unique, little region are artisan producers, varying in profile from low to way-under-the-radar, helps explain its relative obscurity. With well over half a million planted acres, the larger and better-known Paso Robles AVA is a significant contributor to California’s viticultural output. By extension, Adelaida plays a role, even as it sets itself apart. My old friend Alex Villicana has witnessed much of its contemporary evolution, and he has had plenty to do with it.

As the Haas family and their farming and winemaking crews at Tablas Creek have demonstrated over the last three decades and counting, Rhône-Mediterranean red grapes like syrah, grenache, and mourvèdre can make exceptional wines from Adelaida’s vineyards. The same goes for viognier, marsanne, roussanne, and other white varieties of the category. The sub-region’s calcareous, limestone soils and overall milder climate on Paso Robles’ west side allow these vines to express themselves, both in terms of the wines’ complexity and longevity.

When Alex and his wife, Monica, started planting vines in 1997 in a section of the 72-acre Adelaida Hills property they’d purchased the previous year, less than a decade had passed since Tablas Creek’s ambitious project got off the ground several miles away. The couple didn’t exactly have their fellow Adelaida vintners’ Rhône Valley-inspired program in mind, however. The Villicanas’ approach was more Daou/Justin-like, though instead of dedicating their new vineyard entirely to cabernet sauvignon, they also tried chardonnay. “For some reason, I decided that was a good thing to plant when we first got started,” Alex told me over the phone in November after last year’s harvest. Then he laughed. “I found out  really quickly that chardonnay didn’t work.”

really quickly that chardonnay didn’t work.”

He recounted his collaboration with the grapevine nursery the Haases launched in tandem with their winery and wine brand, an operation that started out to suit Tablas Creek’s own vineyard needs but soon turned commercial. “We basically went through one harvest with that chardonnay and then grafted it over to mourvèdre. We just bought the mourvèdre budwood directly from Tablas Creek and grafted it in the field.”

When I emailed Jason Haas recently to fact-check the business side of their nursery, he confessed it was never a money-maker. Writing back, the GM-Partner described the all-Rhône variety nursery in more altruistic terms. “The motivation behind it was to get these high quality clones out into broader circulation, which we were convinced would help the category get itself established in America.”

Jason was talking about a truly American winemaking map of Rhône varieties, not just one of California. As the winery notes on its website, in 1996 the Tablas Creek Nursery started selling its home-grown materials—”high-quality grafted vines and budwood”—to any and all interested growers. Over 600 vineyards and wineries would eventually become nursery customers from wine-producing states like Washington, New York, and Texas, in addition to California

Situated close by, Alex was one such grower interested in Rhône grapes. The budwood he grafted to the ill-conceived chardonnay was an original mourvèdre clone among those the Haas family imported from France for the nursery. That side of Tablas Creek’s business has since shut down, but when he and Monica were getting started growing their own grapes, they became early customers and were (to echo Jason) the recipients of some excellent vine material. Twenty harvests later, the results at Villicana Winery, particularly with its mourvèdre, are impressive

I discovered this for myself last summer. Monica shipped me a couple bottles of their 2018 that pretty much stopped me in my tracks. Right out of the bottle, the combination of aroma and flavor suggested this was a special example of the variety. I knew her husband  was producing a 100% varietal mourvèdre from their vineyard, part of the winery’s Rhône lineup that also includes syrah, grenache, and viognier. But I had no idea how good it would be. It moved quickly to the top of the list of wines I wanted to discuss with its maker.

was producing a 100% varietal mourvèdre from their vineyard, part of the winery’s Rhône lineup that also includes syrah, grenache, and viognier. But I had no idea how good it would be. It moved quickly to the top of the list of wines I wanted to discuss with its maker.

Alex and Monica launched their wine label, Villicana Winery, in 1993, before they were even living in Paso Robles. The California ABC required them to hang a familiar “application to sell alcoholic beverages” notice in an unusual place: the front window of their house in Pasadena, 220 miles south of the hillside property they would purchase and plant themselves three years later. “Our neighbors were a little worried when we posted this,” reads an amusing caption on their website timeline, under a photo of the legal notice. It had to be displayed at the address where the ABC records were kept, which at the time was a quiet, residential corner in Alex’s and my hometown.

It was fitting that when I caught up with him on the phone last fall to chat about his mourvèdre, he was once again filling out ABC paperwork. This time it was for Re:Find, the distillery he founded a decade ago and operates under the same roof as his Adelaida winery. In addition to a range of excellent, grape-based spirits, he makes an ethanol hand sanitizer to help mitigate the infernal covid. He and Monica have donated hundreds of gallons of it around their community.

It was fitting that when I caught up with him on the phone last fall to chat about his mourvèdre, he was once again filling out ABC paperwork. This time it was for Re:Find, the distillery he founded a decade ago and operates under the same roof as his Adelaida winery. In addition to a range of excellent, grape-based spirits, he makes an ethanol hand sanitizer to help mitigate the infernal covid. He and Monica have donated hundreds of gallons of it around their community.

My own covid mitigation method—all mental but, I think, hedonistically on point—has been to seek out and consume quantities of small-production mourvèdres. From Halcón Vineyards in Mendocino County to the Villicanas’ wine to old-school French Bandol, and back to California via my friend Bill Easton’s Amador County version, these are a few of the wildest, most zeitgeisty wines I’ve drunk over the last year.

• • • • •

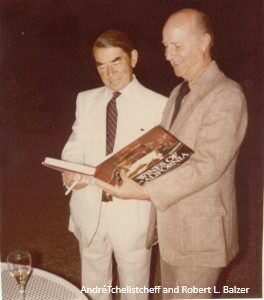

Before either of us turned twenty-one, Alex and I got into wine in somewhat parallel fashion. In 1989, while he was a student at USC, he took a wine course at Lawry’s California Center in Los Angeles. It was taught by Robert Lawrence Balzer, a career restaurateur-retailer and one of the earlier modern wine writers in the U.S. (“early” as in pre-World War II, when he started to put out a wine newsletter for his family’s grocery store; Balzer later graduated up to print journalism, radio, and book-writing, mainly on the subjects of wine and food). “My parents took his classes for as long as I can remember,” Alex said, laughing over the recollection. “I think it was my senior year in college, and he’d been threatening to stop doing the classes because he was getting older. So I actually signed up for his class when I was 20 years old. He kind of looked the other way and let me take it!”

Earlier that same year, I headed to Italy to study for a semester at Syracuse University’s campus in Florence. Just after arriving, I got to spend an evening at the school tasting Tuscan wines in an introductory class led by Aaron Millman, a Washington, DC importer and wine educator. At the time, he was the sole American member of the historic consortium of Chianti Classico producers, which I remember was how he introduced himself. Back in the States, Mr. Millman was known as a passionate importer of French wines, but “one would never guess it by how easily he assumed the role of an Italian country squire,” as The Washington Post’s Ben Giliberti wrote about him in a 1996 obituary. “In Tuscany, he was elected to the technical tasting committee of the Chianti Classico Consorzio, an honor rarely bestowed on an outsider,” the reporter noted.

To this day, I don’t think Syracuse could have found a better ambassador to talk a bunch of beer-drinking, American college students through the nuances of sangiovese and vernaccia. For this former college student, Aaron Millman and his eye-opening evening were forecasters of my future direction. And for Alex, Robert Balzer’s class at the L.A. culinary center was, as he saw it, “when I really started to learn a lot more about wine.” His direction, of course, pointed to winemaking and grapegrowing.

(Another parallel: I remember a ten-pound coffee table book, The Joys of Wine, lying around the house for much of my childhood. The very 1970s tome includes a chapter, “The Wines of California: An Appreciation,” written by Robert Lawrence Balzer. That same copy now lies around our house.)

[Two]

As he recapped his timeline from USC to Paso Robles, Alex mentioned that the head winemaker for a former Paso Robles winery, Creston Vineyards, also sat in the Balzer class and offered him his first winery job after college. That cellar position in 1991 led to him making his own wine at Creston the following year with some gamay he was gifted from a vineyard east of Paso Robles (he and Monica had to harvest the fruit themselves). Then, in the 1993 and ’94 vintages, opportunities came along to purchase cabernet sauvignon grapes from a historic Adelaida vineyard, Hoffman Mountain Ranch.

There are no mentions of Adelaida, let alone Paso Robles, in The Joys of Wine. The Paso Robles AVA, established in 1983, was still something of a blank spot on the California wine map when that door-stopper of a book was published eight years earlier. But across numerous sections of it are references to the famous winemaker-enologist, André  Tchelistcheff, including one in Robert Balzer’s California chapter. The Russian-born Tchelistcheff started his winemaking career in France, but it took off here in Napa Valley in the late 1930s at Beaulieu Vineyard in Rutherford. He went on to become California’s most sought-after consultant of his day, both in cellars and vineyards.

Tchelistcheff, including one in Robert Balzer’s California chapter. The Russian-born Tchelistcheff started his winemaking career in France, but it took off here in Napa Valley in the late 1930s at Beaulieu Vineyard in Rutherford. He went on to become California’s most sought-after consultant of his day, both in cellars and vineyards.

In the early 60’s, one of his more far-flung clients was Dr. Stanley Hoffman, a Los Angeles cardiologist who had acquired 1200 acres of ranch land in the Adelaida Hills. After planting a section of the property with grapevines in 1963, Hoffman hired Tchelistcheff as his consultant. Ten years later, under the guidance of the master vintner, cabernet sauvignon vines went into the ground. And twenty years after that, Alex and Monica found themselves crushing three tons of ’93 Hoffman Mountain Ranch cabernet from those same vines.

Today, there are many connections back to Tchelistcheff and his sphere of influence, particularly in Napa Valley. But the Villicanas’ through-line to this wine industry legend, via Paso Robles, is especially great.

After hearing about the early stage of his career, I understood how working with Rhône or Mediterranean varieties wasn’t Alex’s first choices as a novice winemaker. While the attempt at chardonnay reflected a lack of experience growing grapes, the decision to concurrently plant cabernet sauvignon on his property was better informed by the Hoffman Ranch vineyard nearby and the two vintages he had already made from its fruit. But I think earlier, personal experience had as much to do with it as anything. “I was really fortunate. My dad loved wine while I was growing up,” he said, noting that his father collected it and was a member of the International Food & Wine Society. “A couple of his favorite wines early on were Chateau Montelena and Jordan. He had a cellar full of that stuff. A daily drinker at our house was Montelena cabernet sauvignon. So, you know, when you start with really good wine, it’s easy to fall in love with it.”

Many people who get into wine and, subsequently, the wine business seem to love cabernet—drinking it, of course, but also buying, selling, and making it. For those who find something else to latch onto (which isn’t everyone, and certainly not all winemakers), the floodgates can open wide. In Alex’s case, it has worked both ways. He’s grown and produced Adelaida cabernet sauvignon since those first years of the Villicana label. On their heels in 1998 came merlot and zinfandel plantings, followed by a gravitation towards the Rhône trio of syrah, grenache, and mourvèdre.

Many people who get into wine and, subsequently, the wine business seem to love cabernet—drinking it, of course, but also buying, selling, and making it. For those who find something else to latch onto (which isn’t everyone, and certainly not all winemakers), the floodgates can open wide. In Alex’s case, it has worked both ways. He’s grown and produced Adelaida cabernet sauvignon since those first years of the Villicana label. On their heels in 1998 came merlot and zinfandel plantings, followed by a gravitation towards the Rhône trio of syrah, grenache, and mourvèdre.

Regarding the last of these, I asked him specifically if French Bandol or any other wines based on mourvèdre had moved him to graft that budwood onto his existing chardonnay vines, or if he otherwise had any experience with the variety. “I learned about mourvèdre mainly by growing it,” he replied. “I think it really came down to Tablas Creek arriving here. It opened people’s eyes here in Paso Robles about mourvèdre and other Rhône varieties.”

Though I’ve tasted a number of Villicana wines in the past, mourvèdre was one I had overlooked until a year ago, when I was talking to Joel Peterson about his mataro from Contra Costa County. Those conversations got me thinking about, and then contacting, winemakers I knew personally who also worked with the variety. Several months later, I was pulling the cork on Alex and Monica’s 2018. Their deeply colored, red-black wine—full of wild berries, smoked meat, tar, and other sauvage aromas and flavors—was among the best glasses I poured for myself or anyone else last year (apparently my own floodgates could still open wider). As I’ve covered in this series, some of the other mourvèdres I sought out ended up really grabbing my attention, including Tablas Creek’s Adelaida bottling. This wine showed a little more restraint compared to the Villicana, with slightly lower alcohol. But there was no getting around the characteristics shared by each.

“I think the reason why I like mourvèdre so much, and why I think I like it from our site, is its earthiness,” Alex remarked. He’d just walked me through his red winemaking techniques and then shared some thoughts on how the grape translates from vine to bottle. “It has that sense of terroir, maybe more than any other variety that we grow here in Paso Robles. You can really tell that it’s from this region. You get some of that spiciness and the kind of meatiness that mourvèdre is known for. But I think you can also taste some nice, red, ripe fruit. All of the wines coming off of our vineyard are pretty soft, tannin-wise. I just think it’s got a really good balance to it.”

“I think the reason why I like mourvèdre so much, and why I think I like it from our site, is its earthiness,” Alex remarked. He’d just walked me through his red winemaking techniques and then shared some thoughts on how the grape translates from vine to bottle. “It has that sense of terroir, maybe more than any other variety that we grow here in Paso Robles. You can really tell that it’s from this region. You get some of that spiciness and the kind of meatiness that mourvèdre is known for. But I think you can also taste some nice, red, ripe fruit. All of the wines coming off of our vineyard are pretty soft, tannin-wise. I just think it’s got a really good balance to it.”

Near the end of our call, I brought up Bandol again—the French template for mourvèdre—and suggested we drink one the next time we got together. It was a wine missing from his radar as much as his mourvèdre had been off of mine. Yet, the Villicana was so delicious, I wondered if it really mattered: going back more than twenty vintages, Alex seems to have figured things out in his own back yard.

“It was Tablas Creek and the Haases who showed everybody that this area was so perfect for it,” he reiterated about his Adelaida neighbors and their groundbreaking vine nursery. “So, for me, it was just really about growing it. You know, the surprise to me about mourvèdre was when it was coming off of my vineyard, the intensity it had. It was definitely an eye-opening experience.”

Considering all of Alex’s vintner’s experiences over the last thirty years, impressions of mourvèdre come easily to him. Here was a guy who started his winemaking career soon after college. Then, along with his wife, he planted a vineyard, built a winery, raised two children, established himself as a commercial grower, and built a distillery, all the while serving as a self-described “serial volunteer” to promote the Adelaida AVA for both his own wine brand and his neighbors’. I could excuse him if anything slipped his mind. “I can try to dial mourvèdre in a little bit tighter,” he laughingly apologized at one point. “Unfortunately after so many years, in my brain it all kind of blends together. In the early years, we were just running from pillar to post!”

From what I’ve tasted and observed, Villicana mourvèdre is completely dialed in, both as an important part of the winery’s portfolio and as a crop he sells to a handful of Paso Robles vintners who approach it as seriously as he does. This great wine grape has a firmly established role on his and Monica’s property. He told me during our call that even though he makes what he calls his “Winemaker’s Cuvée,” an atypical blend of mourvèdre and cabernet franc, he really likes to bottle mourvèdre by itself. “When we do get that nice ripeness, I like to leave it as a 100% varietal. I think it’s unique and stands up really well on its own.”

I have to admire Alex’s commitment to mourvèdre, aware, as I am, that cabernet is still king, and that creating “red blends” has become a backup strategy for lots of winemakers up and down California. I certainly didn’t hold back on my praise of his mourvèdre, or hesitate to compare it favorably to other wines I’ve been tasting and profiling. My old friend, who’s now worn a vintner’s hat for a long time, accepted it gracefully and offered some perspective in return.

“Mourvèdre, it’s funny,” he observed. “You say it’s one of your favorite varieties. Since I started growing it, it’s always been one of my favorites. As I said, I grew up drinking cabernet, so that was the grape that I plopped in the ground first. And I still love cabernet sauvignon but, you know, I gravitate toward mourvèdre.”

[End of Part Three — California, Provence, and Australia coming in parts four and five.]

An interesting article, Tony. The one tidbit of info that I noticed was missing was the the involvement of the Perrin family at Tablas Creek. Bob Haas and the Perrins were very close friends and the cuttings for a lot of the vineyard and nursery came from Beaucastel. It was a really interesting experiement from the very beginning!

Paul,

Thanks for reading it, much appreciated! I actually referenced the Perrin-Haas family relationship in part two. Didn’t go into great detail, but it received a mention. -TP